In late 1587, John White bid an emotional farewell to his daughter and baby granddaughter as he prepared to set sail for England. Nearly 50 years old, he was entering the last phase of one’s life for the time but was determined that he would live to return to his family in the new English colony on Roanoke island, just off the coast of modern day North Carolina. He was mayor of the colony, and his granddaughter was the first English baby born in the new world. As the island disappeared over the horizon behind him and the wind rushed through his greying hair, White braced himself for the weeks long voyage and for his mission upon his return to England – to secure desperately needed supplies for the struggling colony of around 115 people.

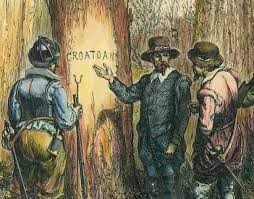

Events out of his control ensured that White would never see his child and grandchild again. He arrived in England at just the wrong time, as the kingdom was gearing up for the feared Spanish invasion and Queen Elizabeth I ordered that all English ships be seized by the state to aid with the defence of the realm. Sure enough, in July 1588 that invasion did come, and despite its sound defeat it was not until two years later that White was able to commandeer a ship and supplies and head back to the colony he had left behind. Upon his return, he found the colony completely deserted. It did not appear that any violence had taken place, because the fences around the colony remained mostly intact and the buildings had been neatly taken apart. Yet there was absolutely no sign of life. The only hint as to the fate of the colony were the ominous letters carved into the fence: ‘CROATOAN.’ It was the name of a neighbouring Native American tribe.

English exploration in the new world

Through the 16th century tales spread across Europe of the unimaginable wealth that the Spanish had found in the Americas, and by the 1580s English explorers were looking at the Spanish riches with increasing jealousy. Though the daring pirate raids on Spanish ships by the likes of Sir Francis Drake re-established some English pride and gave them access to that wealth, it was no longer enough. They wanted to explore the new world themselves. Specifically, English explorers wanted to see what north America had to offer, since the Spanish had all but earnt themselves a monopoly on the south American riches. In 1585, Queen Elizabeth gave permission for Sir Walter Raleigh to organise an expedition to north America but, as one of the Queen’s favourites at court, Raleigh himself was forbidden from joining the venture. Instead, he appointed Sir Richard Grenville to lead the English explorers and find a suitable venue for a colony.

The expedition set sail in April of that year and by July they had been guided by friendly local tribes to Roanoke island, where they established a colony. John White was part of the expeditionary force that year and produced detailed paintings of the landscape, the wildlife and the local American tribes that would later be shown to Raleigh to demonstrate what the explorers had found.

The first colony on the island was to last less than a year. In June 1586, with supplies running low and local tribes becoming increasingly hostile to the settlers, they accepted an offer from Francis Drake to take them back to England. Drake was on his way back from raiding Spanish ships in the Caribbean and had stopped at Roanoke to have a look at the settlement for himself.

Despite the harsh lesson they had learned many of the settlers remained undeterred by the setback, adamant that it was possible to establish a sustainable colony at Roanoke. They were intent on heading back as soon as they could.

The second colony at Roanoke

Raleigh chose John White to take charge of the second expedition to Roanoke, and he arrived back on the island with over 100 settlers, including his pregnant daughter Eleanor and his son-in-law, in August 1587. In those first few months, two momentous events took place that would have given White and the settlers cause for hope. First, White’s daughter gave birth to a baby girl, the first English baby to be born and baptised in the New World. Second, an influential man from the local Croatoan tribe called Manteo was established as the Lord of Roanoke, showing a willingness on the part of both peoples to assimilate and appreciate each other’s political structures.

Despite a generally harmonious relationship with the Croatoan tribe, other local tribes were making their opposition to the colony known and the settlers struggled to find enough food. It became increasingly clear they would not survive the winter without new supplies. So it was that the settlers asked for White to return to England to make a plea to Walter Raleigh, and so it was that White found himself saying goodbye to his daughter and granddaughter for the final time.

It is difficult for people in the modern world to understand the sense of isolation the English settlers would have felt and the anguish that John White would have felt as he stared out to sea for two years, wondering what had become of his family. With no way of contacting each other, all White could do was pray that the colonists were safe, and all the colonists could do was look out desperately for any sign of an English ship on the horizon. They had no idea about the looming Spanish attempt to invade England and would no doubt have feared that John White was lost at sea.

It was not until the summer of 1590, two years after the English had vanquished the Spanish armada, that White was able to set sail again for Roanoke. Arriving on the bright, warm morning of 18th August, he made his way up the beach as fast as his now 51-year-old legs could carry him and found the colony deserted. Not destroyed, but deserted. The only clue about what had happened were the solitary letters carved onto part of the fence that surrounded the colony: ‘CROATOAN.’

Theories

The most prominent theory about what happened was that the colonists, having lost hope of John White returning with supplies, were forced to seek help from the Croatoan tribe and assimilate with them. Indeed, this was the first thought that came to John White and his crew, who tried to sail south to Hatteras, where the tribe was based. However, they were blown north by strong winds and had to turn home. European sailors would for years report that the Croatoan tribe could be spotted at Hatteras waving to them and playing music with European instruments, giving further weight to the assimilation theory.

Another theory attests that the colony was forced to move inland, for fear of being spotted by passing Spanish ships or in order to try and scavenge for food. However, this theory seems unlikely as it would have meant encountering tribes who had left the English under no illusions about their hostility.

Theories that suggest the colonists were killed, either by starvation, plague, or enemy soldiers, do not seem to hold much weight. For a start, there were no bodies found in the area. Even if people had died from starvation or plague and been buried by the survivors, there would still have been evidence of Christian burials around the colony. Secondly, the fact that some of the buildings in the colony had been neatly dis-assembled hints at a calm evacuation, perhaps with Croatoan help, more than it hints at a Spanish or native murder spree.

John White would never return to America again. He died in retirement in Ireland in 1593, heartbroken that he had no knowledge of what had happened to his family. In truth, no one knows what happened to his family and the other settlers. In 2007, American genealogists took DNA from local families to see if they had mixed English and Croatoan ancestry, but the results were inconclusive. The only certainty is that the English settlers at Roanoke were gone by 1590, leaving either by force or by their own choice to head off to an unknown fate.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of History is not an academic source. Our pieces are written by writers who have been keen students of history for years and are well versed in, and influenced by, countless other writers and works. For this article specifically our sources have included:

'What happened to the 'lost colony' of Roanoke?', article published by history.com

'What happened to the lost colony of Roanoke Island?' article by Eric Klingelhofer, published by historyextra.com