It’s the year 1314, and in a dark corner of Paris a group of men are trying to look inconspicuous as they mingle among normal Parisians going about their business. But the men aren’t concerned about what the butcher, the shopkeeper or the baker are up to. These men are spies, and their instructions, which come from the King himself, are far more important than that. Their eyes are fixed not on the streets and alleyways, but on the imposing Tour de Nesle, a tower that stands on the Seine river and keeps watch over the city.

As dusk approaches, the men see what they had been waiting for. A group of three women hurriedly approach the tower, trying to cover their faces as best they can, and wait to be granted entry. Soon after, a man opens the door and ushers the women in, looking around the see if anyone is watching them. The King’s spies are not amateur enough to be caught like this, and the man doesn’t see anything untoward.

He doesn’t know it yet, but he is in mortal danger. His name is Gautier D’Aunay, and he is a Norman knight who keeps watch in the tower with his brother, Philippe. That’s not important in itself, but what is important is the women who have entered the tower, and the purpose of their visit. Two of those women are there because they are engaged in illicit relationships with the D’Aunay brothers. And all three of the women are French princesses, the wives of French princes, the daughters in law of the King.

All five people in the tower that night are playing with fire. And all five of them are about to get burnt.

Background

France at this time was ruled by King Philip IV, who had ascended to the throne in 1285. His nickname was ‘Philip the Fair’, but that name wasn’t given to him because of any character traits. It was given to him because of his physical appearance – he was a striking man; tall, with fair features. ‘Fair’ probably wasn’t how you would describe his character, but then being fair would not have made him a good medieval King. He wasn’t exactly an evil maniac, but he was tough – he knew how to intimidate people, and he knew how to get his own way. Indeed, around the time our story takes place, Philip was engaged in probably his most famous act as King: taking on and crushing the Knights’ Templar, a formidable group of warriors who did not show enough loyalty to him. So already we can see that it wasn’t the best idea to get on Philip’s bad side.

Like any good medieval King, Philip had several children. But for the purposes of this story, we’re only interested in four of them. We’re interested in his three eldest sons – Louis, the heir to the throne, Philip, and Charles. And we’re also interested in their younger sister, Philip’s second daughter, Isabella.

All of them had politically advantageous marriages arranged for them. Isabella married the English King, Edward II, in 1308 – and that marriage is a whole other story in itself. Meanwhile, the three boys were married to noblewomen from Burgundy – Louis married Margaret of Burgundy in 1305, Philip married Joan of Burgundy in 1307, and Charles married Joan’s sister, Blanche of Burgundy, that same year.

So, three sons, three happy marriages, right?

Not exactly. There’s no evidence to suggest that they were all spectacularly unhappy marriages, but they were arranged marriages rather than love matches.

Many spouses in the medieval noble class - usually the husbands - found more excitement outside of their marriages, and affairs were pretty common. Even so, they were still frowned upon, and the consequences for more egregious cases could be pretty severe.

Three princesses, two affairs

All of this takes us to 1313. Although Isabella was Queen of England, she was a regular visitor back to France. I said that her marriage to Edward II of England was a whole other story in itself, but for now I’ll just say that Edward’s ‘close’ relationship with a friend, Piers Gaveston, made Isabella unsure of her position at the English court. So she often met her father to seek advice, and fill him in on what was happening across the channel. Its on one such visit that she arrives in Paris bearing gifts – specially embroidered purses for Margaret, Joan and Blanche. But those purses turned out to be more than just a thoughtful present for her sisters-in-law – they would eventually become the ignition for one of the biggest scandals in medieval Europe.

Later that year, the French royal brothers and their wives attended a banquet in London. The French royal posse was naturally accompanied by numerous people, including two Norman Knights, the brothers Gautier and Phillippe D’Aunay. Isabella was known throughout Europe for her intelligence and attention to detail, and, true to form, she noticed something unsettling about the brothers. She noticed that around their waists hung some fabulous, custom made purses. Exactly the same purses she had had specially made for her sisters-in-law.

There could of course have been any number of reasons for why the D’Aunay brothers were wearing the purses, but Isabella jumped straight to the conclusion that they must be having affairs with her brother’s wives.

She kept her suspicions to herself for the time being, perhaps because she was about to give birth to her son, the future Edward III of England, so she had enough on her plate without accusing her sisters-in-law of adultery. But in early 1314, after she had her baby, she visited France again and informed her father of what she suspected. Philip was outraged at the thought of his daughters-in law betraying his sons, but realised he had better have some proof before he did anything about it. He ordered a group of spies to observe the princesses and the Norman knights and, sure enough, it was discovered that all three of Philip’s daughters-in-law met regularly with the two knights, and that two of them – Margaret and Blanche – were in fact engaged in an affair with them.

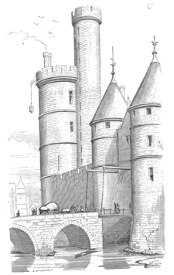

The affairs took place in the imposing Tour de Nesle (wikipedia)

After a period of surveillance, Philip had seen enough. He had the five culprits arrested, and broke the news to an astonished French court. Remember, those themes of chivalry, love and romance were real in medieval Europe, and people did generally aspire to them. Affairs were of course very common, but you weren’t supposed to get caught. And you certainly weren’t supposed to have affairs if you were married to the King’s sons.

The D’Aunay brothers were tortured and swiftly confessed. They were essentially guilty of treason, of causing great offence to the King, and so they had to die. Accounts of their execution in April 1314 vary, but it is known to have been horrendous. They were likely castrated, their genitals thrown to the dogs in front of their eyes in a highly symbolic gesture. Their skin was pulled from their body, their entrails cut from their torso, before they were finally given the sweet release of death by beheading. All of this happened in a public square in Paris, lest anyone else get any ideas about going against the King.

And what of the women? The surveillance had concluded that it was Margaret and Blanche who had had the affairs, and Joan was merely an accomplice who had helped to cover it all up.

Now, executing a pair of knights from Normandy was easily done, but Philip had to be a bit more careful with the women - they were princesses after all. Margaret and Blanche’s heads were shaven in front of the court, in a gesture that was designed to do nothing more and nothing less than absolutely humiliate them. After that, they were packed off to prison. Margaret was dead within two years, while Blanche died in 1328. Her marriage to Charles was annulled soon after the incident.

Joan, however, seems to have been treated a lot more kindly. Her husband, Prince Philip, defended her before the court and begged his father not to punish her. The French King relented, and Joan and Philip remained married, quite happily it seems, until he died in 1322. By that time, he was King Philip V of France. Philip IV died the same year of the scandal, in November 1314.

So, was it all true? It would be tempting to think that it was all malicious rumours designed to bring the women down. But who had the motive to do that? Certainly not King Philip – his court became the laughing stock of Europe after the scandal. It would have been a pretty spectacular own goal if it was him who invented the rumours. Likewise, it is doubtful that his sons would have accused their wives of such lurid affairs. They were mocked mercilessly for not satisfying their women, so again it would have been a pretty terrible own goal if they had just made it all up.

But what about Isabella? After all, it was she who had made the accusations in the first place. What did she have to gain if her sisters-in-law were removed from the picture?

When she told her father of her suspicions, she had just given birth to her son, the future Edward III of England, and it has been argued that she wanted to get rid of her sisters-in-law to decrease the chances of one of her brothers producing an heir, and therefore increase her son’s chances of laying claim to the throne of France somewhere down the line.

It does seem far-fetched. Her brothers were still young men at the time; she must have realised that the marriages could be annulled, her brothers could remarry and produce an heir. But as it turned out, her brothers all died young, and Edward III did in fact lay claim to the French throne. That, my friends, is how the Hundred Years’ War started.

But again, that’s another story. Most historians do believe that Margaret and Blanche were engaged in affairs with the D’Aunay brothers. Of course they weren’t the only members of the nobility to have affairs, but they fell foul of the golden rule: don’t get caught.

Sources:

https://www.historyofroyalwomen.com/france/tour-de-nesle-affair/

https://thehistoryqueen.wordpress.com/2019/04/25/tour-de-nesle-affair/

(Cover image from wikipedia)

.jpg)