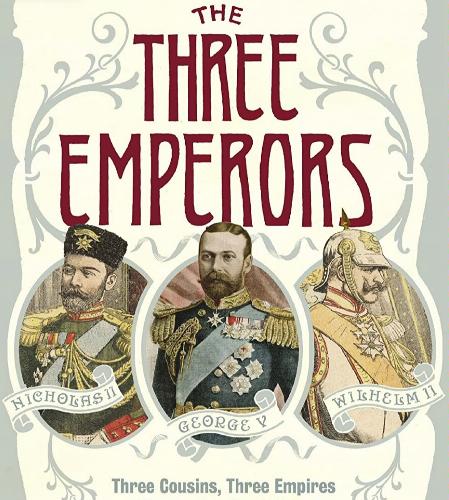

As Europe descended into a state of war in the summer of 1914, three Emperors – all related – sat on the thrones of their respective nations and were discovering, to one extent or another, how powerful they really were. In Britain, King George V waited anxiously for news from his government, and was irritated to find that his annual trips to the Goodwood races and sailing at Cowes were about to be cancelled. In Russia, Tsar Nicholas II was ‘on the verge of tears' as his generals cajoled him into mobilising his army. In Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II was powerless to stop a military which he had hopelessly indulged throughout his reign from jumping headfirst into the war that it had always wanted.

Three emperors who had varying delusions of power, who had varying degrees of actual power, but who in that moment had one thing in common – none of them wanted a pan-European war. Just over four years later, only one would still be sitting on his throne.

Miranda Carter's Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One explores the characters of these three men without whom the origins of the war are impossible to understand, leaning heavily on their own correspondence to give us a fascinating insight into their minds. There is George, the entitled but deeply dull son of the famous extrovert King Edward VII, who was frightened by the 20th century and whose desire to have more influence in governing his vast Empire was juxtaposed with his disinterest in the outside world. Then there is Nicholas, another quiet son of a boisterous predecessor, for whom our sympathy as a devoted family man who was terrified at the thought of being Tsar must be tempered by his disastrous refusal to countenance even modest reform to his backward Empire, and by his brutal suppression of any challenge to his authority. Last, but not least, we have Wilhelm, the desperately insecure and often unintentionally hilarious Kaiser who bounced around Europe convinced of his own diplomatic mastery but left most people he met either completely alienated or thinking he was mad – usually both.

The road to war started long before 1914, and Carter shows us that the complex relations between Europe's royalty is one lens through which it can be understood. Wilhelm, who in 1888 became the first of our three protagonists to ascend to his throne, almost immediately positioned the recently unified Germany as something of an ‘anti-England' in Europe. The tragedy was that he had only become Kaiser, at the tender age of 29, because of the untimely death of his more liberal, pro-British father, Frederick III. Wilhelm had a testy relationship with his parents, and Carter leaves us wondering if his complicated attitude to Britain – veering from outright hatred of the British to a longing to be loved by them, sometimes all in the same day – can at least be partly understood as a metaphor for his turbulent relationship with his English mother, Vicky, the eldest daughter of Queen Victoria. Wilhelm's anti-British posturing, his disdain for Britain's liberal values and democracy, were arguably more of a function of his disdain for his parents than anything else. It seems likely that this macho posturing was also, rather tragically, a way of making up for his deep insecurity about his left arm, which was withered at birth and left him with a life-long disability. Either way, it pushed him further into the arms of conservative Prussian aristocrats, whose influence he could never shake off.

A young Kaiser Wilhelm II, characteristically dressed in military uniform

Next to ascend to the throne – unwillingly, it must be said – was Nicholas, who like Wilhelm was thrust in to power after the untimely death of his father in 1894. Unlike Wilhelm, Nicholas adored his father, Alexander III, who had instilled in him a firm sense that it was his divine right to rule as an autocrat and that any challenge to this right must be ruthlessly eliminated. Young Nicholas, who as a teenager had witnessed the assassination of his grandfather, Alexander II, did not take much persuading. The problem was that while the dominant, decisive Alexander III was equipped to be an autocrat, his son Nicholas was nothing of the sort. Timid, indecisive and uncurious about the Russia that existed beyond his court, Nicholas was a loving husband and father but a truly terrible Tsar. His naivety is at times astounding, his lack of imagination infuriating – all the more so when one is aware of the awful destination his follies are leading him to.

AD:

AMAZON - FOUR BEACH TOWELS FOR £28.49

George became King much later, after the death of his father, Edward VII, in 1910. Indeed, it is Edward who most incenses Wilhelm through much of the book, likely because he was every bit the effortless charmer and diplomat that Wilhelm imagined himself to be. Every diplomatic success that Edward secured was taken as a personal slight by the Kaiser, who scribbled angrily in the margins of dispatches from his ministers. But when he was not raging at the British, Wilhelm was advocating for a grand alliance with them, convinced that Britain and Germany were natural allies, and rushing to his grandmother Queen Victoria's bedside as she lay dying in 1901.

Wilhelm had a tense relationship with his British Uncle, King Edward VII

For his part, Kind Edward found his German nephew utterly tiresome (he was far from alone), and the new King George found him no easier to deal with. He was far happier in the company of his Russian counterpart, who was similar to him in temperament and appearance – George and Nicholas looked so alike that they were often mistaken for one another. Writing letters to each other, ‘Georgie' and ‘Nicky' gossip about and poke fun at their cousin ‘Willy', moaning about what a chore it is to be in his company.

It was not uncommon for Tsar Nicholas (left) and King George (right) to be mistaken for one another

All three men were utterly unequipped to deal with a changing world, but then it was only the Kaiser who really tried to. Carter paints a picture of an incessantly energetic Wilhelm who could hardly stay still for a minute, darting around his Empire to make himself accessible to his people and practising his very best ‘fierce' stare for the cameras. Meanwhile in Britain George insisted that people around him still dress in the style of the 1890s, and in Russia Nicholas cheerfully sipped on champagne after his official coronation in 1896, blissfully unconcerned by the well over 1,000 people who died in a crush during the day's festivities. To George and Nicholas, the outside world was but a frightful rumour.

Perhaps unsurprisingly for early 20th century rulers with 17th century ideas about governance, all three were suspicious of civilian governments. George seethed at the radical Liberal government in London, Wilhelm ranted about the large socialist presence in the Reichstag, while Nicholas, upset that he even had to accept a legislative body in the first place, simply shut it down. In turn, the three men were treated with a mixture of contempt and exasperation by their civilian government officials. This was not such a problem in Britain, where the Liberal Prime Minister Herbert Asquith could patronise the King before leaving him to his stamp collecting, but alas the power of the Kaiser and the Tsar was all too real. It mattered when Wilhelm, filled with a child-like fascination for navy ships, encouraged an arms race with Britain. It mattered that Nicholas was both utterly convinced of his divine right to rule as an autocrat yet utterly incapable of being an effective one. Both Kaiser and Tsar were indulged, ministers who told them home truths were dismissed, leaving Germany in the grip of an over-mighty military and Russia on the verge of revolution.

In this sense, Carter subtly outlines Wilhelm and Nicholas' culpability in the outbreak of war – not because they wanted a European bloodbath, but because it was the inevitable conclusion of their abysmal leaderships. Not that either of them reckons with this as they write increasingly desperate letters to each other in the summer of 1914, in a vain attempt to avert catastrophe.

And what a catastrophe it would be, for Nicholas in particular. Against all advice, he personally took the reigns of the Russian war effort and proved that he was just as bad a wartime leader as he had been a peacetime leader. In early 1917, faced with a mutinous army on the front and a revolution at home, reality finally caught up with our hopeless Tsar and he was forced to abdicate. Stuck in revolutionary Russia in the hands of a government that wants to get rid of them, the royal family were offered sanctuary in Britain.

But there was one person who was not too keen on the idea – Nicky's best royal friend, King George. Carter shows that George's primary reason for refusing them sanctuary was self-preservation; he was petrified that providing sanctuary for the Tsar, who was not particularly popular in Britain, would lead to a British revolution. Not only this, but George was happy to let others take the blame for his betrayal, which was not known about until fairly recently. Indeed, it was the new Prime Minister David Lloyd George, the radical Welsh Liberal who George so despised, who took the brunt of the blame, despite the fact that he had supported the idea of providing a home for Nicholas and his family. Lloyd George took the King's dirty secret to the grave with him – a seemingly odd turn for a true class warrior who had previously basked in George's hatred.

By the end of the year Nicholas, his wife Alexandra, and their five beloved children were in the hands of the newly formed Soviet government. In July 1918 they were summarily executed in a basement in Siberia.

Nicholas and his family were brutally murdered by revolutionaries in 1918

The Kaiser was still Kaiser at this point, but in name only. There was no taking control of the war effort for Wilhelm who, for all his aggressive rhetoric, ‘could not lead three soldiers over a gutter' and had desperately tried to avoid war as soon as he realised it would be on a Europe-wide scale. Almost immediately side-lined by the generals who had used him to get their war, Wilhelm spent the next four years being patronised by them. They never told him of their plans, speaking to him only to assure him the war was going well and to ask for his signature on orders they had written themselves. Unusually for a man so given to self-delusion, Wilhelm was acutely aware of his irrelevance; ‘if people in Germany think that I am supreme commander', he growled in November 1914, ‘then they are grossly mistaken'. Nonetheless, he was still keen to project an image of control to the outside world, insisting that those around him ‘maintain the fiction that I order everything'. He was forced to abdicate just days before the end of the war in November 1918, and fled to exile in the Netherlands. There he would remain, sulking about the injustice of it all, until his death in 1941.

The happiest ending was reserved for George, who remained King until his death in 1936. It is no accident that the only constitutional monarch of the three was the only one still standing by the end of the war. By any standard George was a boring man who never threatened to stand in the way of the modern world (even if he wasn't happy about it), and during the war he set the template for the modern British monarchy, offering Buckingham Palace as a hospital for wounded soldiers, visiting soldiers on the front and factory workers at home, and generally relaxing into a purely ceremonial role. This would never have stood for the Kaiser and the Tsar, who were consequently washed away by the sweeping social movements that would surely have got rid of them anyway. The war had only hastened, rather than caused, their demise, and the demise of the archaic world they clung to.

Three Emperors: Three Cousins, Three Empires and the Road to World War One

Miranda Carter, 2009

http://mj-carter.com/us/books/the-three-emperors