Who discovered America? Well, the native Americans of course. But after that, who? The obvious answer is Christopher Columbus, the Italian explorer who promised to find a quicker route to the far east and ended up finding the Caribbean. The clever among you may suggest it was in fact the Vikings who were the first Europeans to reach America, as the famous Leif Erikson is widely thought to have set foot in Newfoundland hundreds of years before Columbus set sail. But Erikson’s stay was brief, and he and his fellow Vikings made no attempt to settle in America, instead scampering back towards Greenland, Iceland and Scandinavia. So, who were the first Europeans to settle in America?

The answer could be unexpected – quite possibly, the first European settlers in America came from Wales. Legend has it that a 12th century Welsh prince, Madoc, travelled west across the Atlantic with a band of settlers and returned with tales of a fantastic new world he had discovered. He collected more of his people and set sail again, never to return to his native land. The story was widely told in Wales and the rest of Britain through the centuries but never taken too seriously, until the 18th century when European settlers discovered a new Native American tribe, the Mandan. They had a noticeably fairer complexion to other native peoples and spoke a language that was similar to Welsh, raising an astonishing question – could the obscure legend about Prince Madoc really be true?

The Legend

Prince Madoc was disgusted with his violent siblings

For background to the legend, we turn to Ben Johnson's article for Historic UK. Madoc was said to be a son of Owain Gwynedd, an historically verifiable and important ruler in Wales who resisted the English King Henry II’s advances on Welsh lands. The story goes that when Owain died in 1170, his children engaged in a deathly struggle with each other to replace him, but it was a struggle that Madoc and one of his brothers, Rhirid, wanted no part of. Disgusted at the violence and scheming their siblings had resorted to, they gathered ten ships and sailed into the Atlantic, heading west to see what they would find. Madoc returned to Wales in 1171 to tell his people what he had found – supposedly modern day Alabama – and gathered more settlers for his return journey. He and the people who followed him were never heard from again.

The story of Madoc and the mystery land he had discovered was passed down through the generations, but really started to gain traction in 1580 when a doctor, John Dee, repeated it to Queen Elizabeth I of England and suggested that the land Madoc had discovered was in fact America. The Queen, whose grandfather Henry VII was a Welshman, was delighted at the thought that the new world had been discovered by people from the British Isles and encouraged the spread of the legend.

How true is it?

The legend was widely circulated and many British explorers were desperate for it to be proved right, so the ‘proof’ that people came up with should be taken with a pinch of salt. Even so, there does seem to be some convincing evidence that there was some Welsh influence in America long before Europeans arrived en masse.

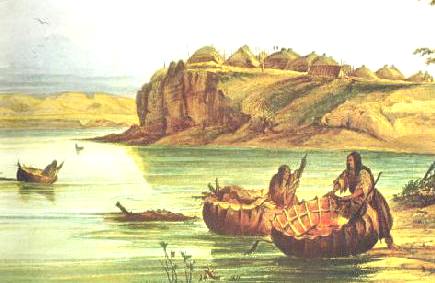

In the early 17th century, English explorers who ventured further inland from Virginia were adamant that they heard Native Americans speaking a coarse language that was similar to Welsh. This could of course be put down to their eagerness to give more legitimacy to the Madoc legend, but the case was strengthened a century later with the discovery of the Mandan tribe. The Mandan lived in what is now Alabama, and had noticeably fairer skin than other native tribes. The language they spoke was indeed strangely similar to Welsh – so similar that in later years Welsh speakers who were brought to the area could easily have conversations with Mandan people. While other native tribes were nomadic and built structures made primarily of wood, the Mandan lived in purposely laid out towns and villages, some of which were dotted with European-style stone forts that later analysis showed were constructed in around the late 12th century – exactly the era that Madoc was said to have settled in America. The Mandan also fished in small vessels that were identical to coracle boats – a distinctly Welsh invention – and even their very name could be said to have derived from the Welsh prince.

The Mandan fished in small coracle boats and developed permanent settlements

For most explorers, the discovery of the Mandan tribe was proof enough – Madoc and his Welsh followers had indeed settled in America before any other Europeans. The tale was spread further by 19th century writers such as George Carlin, who speculated that the Welsh people had arrived in the Mobile Bay in Alabama and mixed with the native population.

Of course, this was all well before scientific progress gave us the ability to test the ancestry of the Mandan people and settle the issue once and for all. So, has such a test been carried out? Unfortunately, no. A terrible smallpox epidemic killed virtually the whole tribe in 1838, and the handful of survivors were either sterile or forced to mix with other people, thus compromising any Welsh DNA they may have had. The case therefore remains unproven, yet tantalisingly probable. After all, what are the chances that an obscure Native American tribe in Alabama could have had so many apparent connections to Wales?

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of History is not an academic source. Our pieces are written by writers who have been keen students of history for years and are well versed in, and influenced by, countless other writers and works. For this article specifically our sources have included:

'The discovery of America...by a Welsh Prince?' article by Ben Johnson, published by historic-uk.com

Images

Image One - warpaths2peacepipes.com

Image Two - Geni.com