England has made a lot of enemies throughout history, as her subjects have turned up in lands near and far and not always been on their best behaviour. But in order to reach those faraway lands England first had to wrestle with other ambitious Europeans to assert military and naval dominance; and at least in this story, England had made an enemy by being a rival coloniser rather than just a coloniser.

In the mid-17th century, England was locked in a commercial battle with the Netherlands. Emerging from the turmoil of the civil war, Historic UK notes that the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 led to a surge in nationalism and a renewed effort to assert dominance over the Dutch after the first Anglo-Dutch war in the early-1650's. A second war broke out in 1665, and the English seized a Dutch settlement in the new world. The Dutch had named their settlement ‘New Amsterdam', but when the English took over they gave it the name by which it is still known today – New York.

Despite this, 1665 was not a good year for England as the great plague killed thousands in London. The following year, the Great Fire of London tore through the city and left thousands homeless and penniless. These two humanitarian catastrophes were also economic catastrophes, disrupting trade in the capital and therefore limiting the treasury's tax revenue. As the government's cash dried up, it could barely afford to pay the soldiers and sailors needed to prosecute the war against the Dutch.

AD:

LUXURIOUS BEACH TOWELS READY FOR YOUR SUMMER HOLIDAY

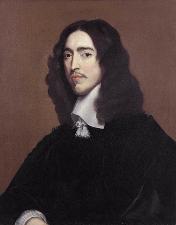

In the Netherlands it was decided that this was the perfect time to strike against a demoralised enemy, and an audacious plan was devised by the statesman Johan de Witt. Somewhat of a Dutch golden boy having become the political leader of the Netherlands at just 28 years old, de Witt was now 41 and at the peak of his power, keeping the Orange monarchy at arms' length and still five years away from a swift fall from grace which would result in he and his brother being savagely murdered by a mob in Amsterdam. He decided to go for the jugular and attack the English fleet at Chatham, along the river Medway just south-east of London.

The Dutch Republic was led by Johan de Witt (image from wikipedia)

On 6th June 1667 English fishermen reported the sight of the Dutch fleet just off the Thames Estuary, but inexplicably the admiralty in London was not alerted. The alert only arrived on the 9th June when 30 Dutch ships approached Sheerness and duly captured the fort there, but by then it was far too late. A large iron chain that spanned the river Medway was desperately lifted in an attempt to prevent the Dutch reaching Chatham, but, under the command of the famous Michiel de Ruyter, the Dutch fleet smashed through the chain and the paltry English resistance.

The route that the Dutch fleet followed (image from wikipedia)

By 12th June the Dutch had reached Chatham. Despite fierce cannon fire from an English garrison stationed at Upnor Castle, they managed to sink or destroy some of the Royal navy's most prized ships, including the Royal Oak. The situation was so desperate that the Duke of Albemarle, George Monck, who had been hastily dispatched from London to oversee the port's defence, ordered around 20 Royal Navy ships purposely sunk so that they did not fall into Dutch hands. This was perhaps in response to his witnessing the biggest humiliation of the entire raid – the Dutch capturing King Charles II's flagship, the Royal Charles.

The town was flooded with English infantry, cavalry and artillery on 13th June, which prevented Dutch sailors from disembarking and completely capturing the port. But the damage had already been done. Satisfied with a splendid few days' work, the Dutch withdrew on 14th June, with the English flagship towing behind them and a scene of devastation in their wake.

AD:

THE DEFINITIVE VISUAL HISTORY OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND

Despite the decisive victory for the Netherlands, the raid on Chatham represented a turning point in the commercial and ultimately imperial ambitions of both nations. In the short term, England was forced to sign a peace treaty in the town of Breda on 31st July 1667, which brought hostilities to an end and seemed to secure Dutch superiority. But in the long term, 1667 would prove be the high point of the Dutch ‘golden age', and the Netherlands would never again enjoy such dominance. Their cultivation of a successful navy had come at the expense of creating a capable land army, and a calamitous defeat to the French on land in 1672 – a year the Dutch named rampjaar (‘disaster year') – saw their era of supremacy come to a shuddering end. The resulting political upheaval saw the House of Orange attain power through William III, and saw a brutal end for Johan de Witt; blamed for the Dutch defeat to France, he and his brother Cornelius were lynched by a mob in Amsterdam that August.

In England, the humiliation at Chatham was the spark for a period of sustained investment in the Royal Navy which resulted in British domination of the seas (after the 1707 act of union between England and Scotland). It is not a stretch to say that the destiny of England, the British Isles, and a quarter of the globe was altered over a few violent days in the summer of 1667.

Acknowledgements

Historic UK, ‘Raid on Medway 1667' https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Raid-On-Medway/

Cover image from BBC