In June 1920, a chilling headline hit newspapers in Britain, and as far away as Singapore and New York. Cuthbert Lucas, a Brigadier General in the British army, had been captured by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). People knew this meant almost certain death, and when she saw the headline Lucas’ wife was so distressed she went into premature labour. Her family had known of the capture for a few days but tried to hide it from her.

Yet the Lucas family needn’t have worried. They had always known their Cuthbert was a charming individual, but what they could not have known was that his charm would work so well on his Irish captors. Instantly befriending the men who probably had orders to kill him, Cuthbert Lucas spent many a night drinking and playing poker with them. While the British army swarmed across Ireland to try and find him, his captors moved him from safehouse to safehouse and ran huge risks to their own lives in order to ensure Lucas could write to his wife regularly and receive her replies. After a month he managed to ‘escape’, almost certainly with help from his new IRA pals, and headed back to England where he refused to name any of them. His only comment was his cheerful declaration that he had been ‘treated like a gentleman by gentlemen.’ It was truly an incredible tale.

Who was Cuthbert Lucas?

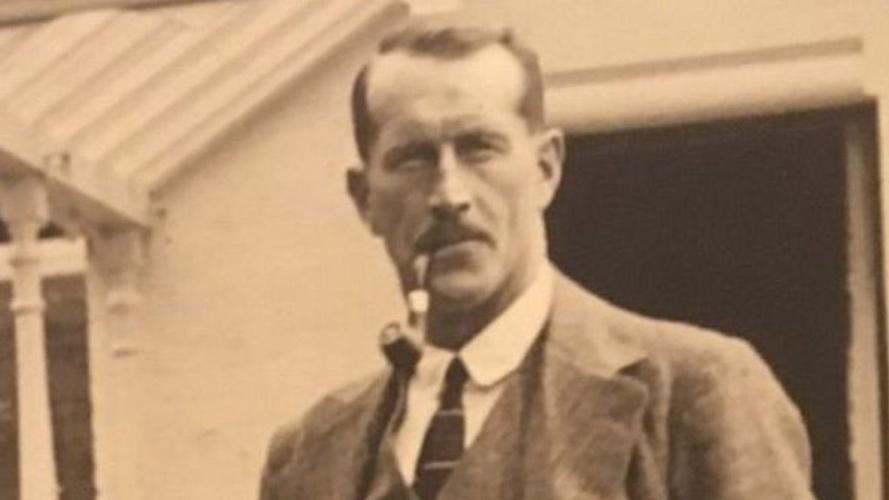

This image of Cuthbert Lucas was taken during WWI (BBC)

Cuthbert Henry Lucas was born in Hertfordshire on 1st March 1879 and embarked on a military career as soon as he left school. He was sent to South Africa during the Boer War (1899-1902), after which he was stationed sporadically in British African territories for the next decade. He served for the entirety of the First World War, fighting at Gallipoli in 1915 and the Somme in 1916, while also finding time to court Joan Holdsworth, who was known to her family and friends as ‘Poppy’. The couple married in October 1917.

Lucas was a tall, handsome man with a neatly trimmed moustache and a dapper sense of style. He was a born leader who had a happy mix of natural charisma and a sense of fun, and by all accounts was a genuinely nice man. People liked him, and this was a quality that would save his life.

He had barely had time to catch his breath after the end of the First World War before he was posted to Ireland to fight for the British in the Irish War of Independence. By the end of 1919 he had taken command of a barracks in Cork, which is where his extraordinary tale of captivity began.

Capture in Cork

26th June 1920 was a warm day in Cork and Cuthbert Lucas took full advantage of a spare few hours by heading down to the River Blackwater near Fermoy for some fishing. It was while he was sitting here, totally alone and unprotected, that he was approached by several IRA men and abducted.

The story that followed had a happy ending but there was no way Lucas could have known that at the time. Ireland was gripped by violence in 1920 and both British and Irish soldiers were guilty of unspeakable atrocities, so he likely expected to be killed very shortly and one can only imagine the terror he felt at his capture. However, this was not the first dangerous predicament he had found himself in and he swiftly regained his composure, and it did not take long for an outgoing man such as him to start talking with his captors. While they laid low in a safehouse in rural Cork, Lucas and the IRA men gradually built up a rapport, so much so that they went fishing together by day and played poker by night.

Meanwhile, news of Lucas’ capture had spread and the British army poured huge resources into trying to rescue him. The situation became too precarious in Cork so he was moved to Limerick. Still, despite the fact that the Irish countryside was swarming with British troops, Lucas was allowed to spend much of his day outdoors, even giving tennis and croquet lessons to the IRA men. He also received a bottle of whiskey a day – standard allowance for a prisoner of war of officer class – and, perhaps most shocking of all, was allowed to write home to his wife.

The British army had notified Lucas’ family of the capture but a decision was made to try and shield the news from his heavily pregnant wife Joan until she gave birth. But once the story reached the media, there was no chance of Joan not finding out. The story reached Singapore and New York, and nearly every British newspaper had it on their front page, and Nic Rigby explains that sure enough Joan saw the headline one morning at the end of June while staying with Lucas’ parents. She was so distressed that she went into labour prematurely, but gave birth to a healthy baby boy, the couple’s first child. She then had her anxiety relieved by a letter which arrived from her husband, who reassured her that she was not to worry, that he was being well treated, but he was very bored.

Joan excitedly wrote back to Cuthbert with news of the birth of their son, and the couple continued to converse for the following few weeks. They were allowed to do this by the IRA employing an elaborate scheme of code names and stolen stamps to ensure the couple’s letters reached one another, showing the extent of the friendship they had built with their hostage. This was a privilege they never granted to other prisoners, and they were allowing the letters at a huge risk to themselves.

What is striking about Cuthbert Lucas’ letters is how unbothered he seems about his situation. Of course, this could have been merely a façade to reassure his wife, but there is a sense that he is genuinely calm. As detailed by Catherine Sanz, in one letter he delights in telling her about the new razor and soap he has been given, and in another he even muses that Joan ought to be looking for houses for the couple to purchase when he returns to England. These are not the things one might expect an IRA captive to be so concerned about.

By the middle of July Lucas had been moved to County Clare, but the effort to keep him hidden was taking up too much manpower for the IRA to tolerate for much longer. That usually meant the captive would be shot, but the men did not want to kill Cuthbert Lucas. On 30th July, he ‘escaped’ his captivity in Clare and reached a British army station, and he was transported back to England amid much publicity. The British press had a field day with stories of Lucas’ daring escape, but in reality his captors had basically let him go. It is a phenomenal testament to Lucas’ character that they allowed him to escape, as these were incredibly tough men who would not have thought twice about killing any other British soldier. Lucas appears to have been a genuinely likeable man.

Lucas returned to his wife, Joan (BBC)

Cuthbert Lucas remained in the army until 1932 but was never again posted to Ireland. He settled in Stevenage with Joan and their children and died in 1958. He refused to ever give details about any of his IRA captors, insisting that they were good men who just happened to be on the other side of a grim war. As a professional soldier Lucas understood the Irishmen were doing their duty and that it was only his charm and ability to be liked that had saved his life. It also made for an incredible story.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of History is not an academic source. Our pieces are written by writers who have been keen students of history for years and are well versed in, and influenced by, countless other writers and works. For this article specifically our sources have included:

'Fishing, Croquet and Poker: just a usual day for the IRA's favourite prisoner', article by Catherine Sanz, published by The Times (2019)

'The Army general who charmed his IRA kidnappers', article by Nic Rigby, published by BBC News (2019)