It was raining heavily as dawn broke over Boscobel House, near the Shropshire-Staffordshire border, on 6th September 1651. Two men hurried through the field outside the house, shielding themselves from the elements and heading straight towards a large oak tree. They would stay there, having hauled themselves up to some secure branches, until night fell again.

Why did the men stay in a tree all day? Because they were hiding. One of the men was 21-year-old Charles Stuart, son of the recently executed King, Charles I. The new ruler in England, the ‘Lord Protector’ Oliver Cromwell, was intent on capturing Charles and almost certainly planned to execute him, so that he could not threaten his position. His men knew the prince was in the area and were swarming around the woods and country estates to try and find him.

Charles would not be captured that day, or any other day. That dreary September morning he was only at the beginning of a six-week long odyssey around central and southern England, relying on a series of loyal friends and comic disguises to keep him hidden from Cromwell’s men, before finally finding safe passage to France. Eventually, he would return to England as King Charles II, and he would delight in telling guests at his court about his daring and sometimes bizarre six weeks as a fugitive.

Why was Charles a wanted man?

Charles Stuart’s father, Charles I of England, had fought against Parliamentary troops in the English Civil War (1642-1651) and lost. He was executed in January 1649, and though his son and a handful of loyal royalists, with support from Scotland, kept fighting until the middle of 1651 it was clear that the cause was lost. In the meantime, a general from the victorious Parliamentary army, Oliver Cromwell, had been proclaimed the Lord Protector of England and been given much of the powers of the old King. He was intent on wiping out any remaining royalists, and Charles Stuart was top of his target list.

Oliver Cromwell was appointed 'Lord Protector' of England (wikipedia)

Charles had been exiled by his father for his safety in the late 1640s but, upon hearing of his father’s execution, took it upon himself to return and re-claim the throne. He arrived in Scotland in 1650 and was able to raise support, but, as Charles Spencer explains, he spectacularly misjudged how popular he was in England. Far from welcoming back the rightful heir the throne, most of the English royalists who had fought for his father were reluctant to get involved in another war, and all the English public could see was a terrifying invading Scottish army. Charles was dismayed at his lack of support but kept marching further south, and in August 1651, having been turned away by every other town, he finally found a town that would accept him and his army – Worcester, in the west Midlands.

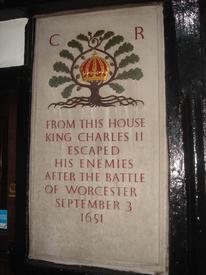

Oliver Cromwell heard where Charles and his army were based and quickly marched to meet them. The battle of Worcester took place on 3rd September, and ended in a crushing victory for Cromwell. Charles desperately tried to persuade his remaining army to stay and fight, but everyone knew the cause was lost. Most of the surviving Scots tried to escape but were captured by Cromwell’s men, who had formed a net around the town. Escape for Charles seemed impossible, especially given his striking features – he was about 6 foot 2, incredibly tall for the time, and had a famously big nose and prominent lower lip. Having escaped his lodgings – a building which is now the King Charles pub in Worcester – through a back door as Cromwell’s forces swarmed the town, he and a few men managed to escape the town under cover of darkness and he tried to disguise himself as a peasant. He cut his hair, made his face dirty and – most painful for Charles – crammed his feet into an uncomfortable pair of shoes, a far cry from the regal footwear he was used to.

A plaque marks Charles' escape from a pub in Worcester (wikiwand.com)

Charles initially wanted to head to London, but was told in no uncertain terms that this would be impossible. Instead, one of his men, Lord Derby, suggested they seek help from a Catholic family he knew near Worcester who had a history of hiding Catholic priests in their home. Though a Protestant himself, Charles would quickly learn that his best hope of escape was with the help of the Catholic underworld.

First Days on the run

Charles reached Boscobel House, home of the Penderel family, on the morning of 4th September. Another family might have turned him in straight away but, luckily for Charles, the Penderel’s did not hesitate in helping him. However, it was quickly decided that Charles would stand a better chance of surviving if he was not accompanied by a band of men, so many of his closest companions went their separate ways to try and save their own skins. Most, including Lord Derby, were captured and executed.

The tree in which Charles hid no longer exists, but this tree was planted on the exact same spot (alamy stock photo)

The tree in which Charles hid no longer exists, but this tree was planted on the exact same spot (alamy stock photo)

The Penderel family decided to disguise Charles as a farm labourer, which again meant him squeezing into a tiny pair of shoes. By the end of the day Charles’ feet were bleeding and he was in excruciating pain. They tried to teach him the local accent and had a heart in mouth moment when a maid from the farm told them she had been approached by Parliamentary soldiers asking of Charles’ whereabouts. On 5th September, a former colonel in Charles’ army named William Carlis reached Boscobel, and he brought news of the Parliamentary army raiding houses in the area and suggested they hide in a tree for the day. Charles later commented that during the day he could see Cromwell’s men ‘peeping out of the woods every now and then’, and one cannot imagine the terror the pair of them felt, trying not to move or make a sound and praying that the branches would hold their weight, as they watched the men search the woods around them. That night, they were forced to sleep in an uncomfortable ‘priest hole’, which the Penderel family had used for nearly 100 years to hide Catholic priests. It was a particularly uncomfortable night for the unusually tall Charles.

On 7th September, it was suggested that the King move to Moseley Hall, which was occupied by another Catholic family, the Whitgreaves. It was here that a Catholic priest named John Huddleston tended to Charles’ feet and he was able to sleep in a proper bed for the first time in days. However, danger was still lurking. On the afternoon of 8th September, a band of Cromwell’s men arrived at the hall and Charles was forced to desperately clamber into a tiny priest hole. The family patriarch, Thomas Whitgreave, was able to convince the soldiers that Charles was not with him, but Charles decided the hall was too dangerous. He had to move again.

Jane Lane and the attempted escape from Bristol

On the morning of 9th September Charles and a friend, Lord Wilmot, arrived at Bentley Hall, near Walsall. The hall was the residence of Colonel Lane, who had fought alongside Charles’ father during the civil war, and his sister Jane Lane. Jane had a permit to travel to Bristol to visit a friend who had just had a baby, so it was decided that Charles would be disguised as Jane’s servant before trying to find a ship headed for France from Bristol.

The party – Jane, Jane’s sister and brother-in-law, Charles, and Lord Wilmot – set off on 10th September, and Charles was forced to think on his feet as his real identity threatened to be revealed. Along the way, one of their horses lost its shoe and, as the ‘servant’, Charles was forced to take the horse to a blacksmith. He later recalled that he asked the blacksmith if there was any news about the rogue prince; the blacksmith, after joking about how many Scots had been killed, replied that there was nothing new to report. Charles allegedly swore that the prince ought to hang like a dog, to which the blacksmith responded positively. In the next town along, the party were forced to hold their nerve and calmly weave their way through a whole Parliamentary cavalry regiment who were drinking outside a tavern, and when they stayed the night at a relation of Jane Lane’s Charles was forced to help with the household servants.

The party reached Bristol on 12th September, only to find that there would not be a ship departing for France for another month. It was decided that they should now head for the south coast, and luckily Charles and Lord Wilmot knew a family who they could stay with on the way. The Wyndham family had fought for the royalists in the 1640s, and one of the Wyndham brothers was married to the daughter of the nurse who had looked after Charles when he was young. They stayed with the Wyndham family in Trent, a small village in Dorset, where Jane Lane and her family departed the group.

Attempt to escape from Chartmouth

The Wyndham family knew a merchant family in Chartmouth, a port town in Dorset, who informed them that they had a tenant who was due to sail to France in a week’s time. On 22nd September, Charles rode with one of the Wyndham women, Julianna, to Chartmouth, under the guise of being a runaway couple. The tenant knew of their real identity and agreed to take Charles to France, but made the mistake of telling his wife about the plan. The following morning, his wife locked him in the house and refused to let him leave, fearing the consequences if it was discovered he had helped the prince escape.

When Charles and Julianna were left with no ship to board in Chartmouth they rode to nearby Bridport, still hoping to find a ship bound for France. They had no luck, and Charles was forced to spend the next two weeks back at the Wyndham family home in Trent.

Escape from Shoreham

By 12th October, Lord Wilmot had arranged for himself and Charles to be taken to France on a coal ship that was due to sail from Shoreham, on the east Sussex coast, in three days’ time. This was quite a distance to make up and there was not a minute to lose, so they set off in the early hours of 13th October. There was still time for one last heart-stopping moment – a group of Cromwell’s cavalry looked as if they were charging directly at Charles and Lord Wilmot, but they breezed straight past them. On the night of 14th October the men arrived at an inn in Brighthelmstone, now known as Brighton, where they met with the captain who was to take them to France the next day.

The drama was not over yet. The inn keeper happened to be a former royal servant, who recognised Charles and bowed instinctively before him. Upon realising who he was, the captain of the ship was furious about the danger he had been put in and demanded extra payment. Charles swiftly agreed, and at 7 o’clock the next morning, as dawn broke over a calm sea, Charles finally escaped from England. Not two hours later, Cromwell’s men arrived in Shoreham hunting for him.

What happened to Charles after his escape?

Charles arrived in France the following morning and went to Paris where he was re-united with his mother, who had been fretting for weeks about the fate of her son. He stayed in France for over eight years, until he was invited by the English Parliament, populated with many men who had once been intent on capturing and killing him, to return to England as King Charles II in 1660. Oliver Cromwell had died in 1658.

Nearly ten years after his escape, Charles Stuart returned to England as King Charles II (onthisday.com)

Charles delighted in telling everyone about his six weeks on the run, and though some of his anecdotes (his conversation with the blacksmith, for example) may have been exaggerated, one can hardly blame him for being proud of the story. He showered gifts on the families who had helped him, including the Penderel’s, the Wyndham’s and the Lane’s, inviting them to court regularly and giving them each a special coat of arms. His time on the run had also exposed him to common people who he would otherwise never have met, giving him a sense that he was in touch with his people.

Charles also knew he owed his life to Catholics, who had stepped up to help him when all others had abandoned him. As such, though he remained a Protestant he was far more religiously tolerant than most monarchs of his time, and even married a Catholic. As he lay on his deathbed in February 1685, Charles secretly confided in his Catholic brother, James, that he wanted to be converted to the faith before he passed away. James entered the room soon after with none other than Father John Huddleston, the priest who had tended to Charles’ feet at Moseley House over thirty years previously. James brought him to the King with the words ‘this good man once saved your life. He now comes to save your soul.’ Charles smiled, and was given the last rites by Huddleston.

Despite their wealth and power, many Kings at this time did not exactly live sheltered lives – most were expected to fight with and lead armies, for example. Yet most monarchs never had to endure six weeks on the run in their own kingdom, hiding in trees and using various disguises, with the knowledge that one mistake would lead to certain death. Though he talked about his ordeal in later years as if it was a spectacular gap year, Charles Stuart knew more than anyone how terrifying it had been. As he sat on his throne and spoke fondly about those six weeks in his twenties, he could justifiably have felt that he had earned his position more than most.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of History is not an academic source. Our pieces are written by writers who have been keen students of history for years and are well versed in, and influenced by, countless other writers and works. For this article specifically our sources have included:

'Charles II and the Royal Oak', article published by english-heritage.org.uk

'Charles II's great escape', article by Charles Spencer and Charlotte Hodgman, published by historyextra.com (2017)

'Charles II hides in the Boscobel Oak', article by Richard Cavendish, published by History Today (2001)

.jpg)