‘The one bright spot was the settlement of the Irish strife. God moves in mysterious ways…'

So confided British Prime Minister Henry Herbert Asquith to his diary on 3rd August 1914. Europe was moving toward catastrophe at a frightening pace, and his government would declare war on Germany the next day. Contrary to popular belief, the government and military top brass were never under any illusion that this would be a quick war; there was an understanding that there would be stalemate and slaughter on an industrial scale. But in the corridors of power in London the fear and dread were mixed with an unmistakeable sense of relief: at least they wouldn't have to think about Ireland for a while.

On the recent series on Ireland on the Rest is History podcast, guests Paul Rouse and Dan Jackson both made the point that the first world war interrupted a dispute over Ireland that was fast reaching crisis point. The Liberal government, whose ability to govern depended on support from Irish nationalist MPs, had passed a Home Rule bill in the face of vehement opposition from Irish loyalists and their supporters in the Conservative party. Both sides were locked in a stalemate, paramilitaries were starting to form, and the British army was threatening to mutiny.

The first world war changed everything, and in our understanding of modern history there is a before and an after. The popular memory of the ‘before' period is of a long Edwardian summer, of music halls and picnics, days at the beach and at the races. As Andrew Marr put it in his masterful Making of Modern Britain, this image is not completely false – ‘fun was had' – but there were dark clouds on the horizon ‘almost everywhere you looked' in Edwardian Britain. The suffragette campaign was at its zenith, the labour movement was growing, the political class was being torn apart by arguments over welfare and constitutional reform, and in the aftermath of the Boer War there was panic that the new century would see Britain overtaken as the world's great power. But the most dangerous threat, an existential threat, to the United Kingdom was posed by the dispute over the Irish Home Rule bill, and the increasingly militant opposition to it.

What was Home Rule?

Home Rule would have given Ireland self-governance within the United Kingdom. Ireland had had its own parliament in Dublin until 1801 when it became part of the UK. A Home Rule bill would have allowed a parliament to sit in Dublin again and control Irish affairs, but Ireland would have remained part of the UK and still sent MPs to Westminster.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, support for the Home Rule movement generally split down religious lines, with Catholics in Ireland in support of it and Protestants opposed. But to reduce it to this would be to do an injustice to the complexity of the issue and the history of British-Irish relations – indeed, the leader of the movement in the late 19th century, Charles Stuart Parnell, was an Anglo-Irish Protestant. While religion was certainly a solid indicator of how one felt about Home Rule, one's wider politics was too.

A bill was first introduced in the House of Commons by Prime Minister William Gladstone in 1886, but it was defeated and eventually led to a split in his Liberal party. The Conservatives were able to dominate British politics for the next 20 years, although during a brief spell of Liberal government in the 1890s a bill did pass through the Commons (only to be thrown out by the House of Lords). But in 1906 the Conservatives suffered a devastating defeat to the Liberals, who were promising a radical redefinition of the role of government and eventually of the constitution itself.

How solid was Liberal support for Home Rule?

William Gladstone's support for Irish Home Rule had come from a sincere belief in its righteousness, but the new generation of Liberals were not so persuaded. The main men in the cabinet were the arch-imperialist Winston Churchill, the devoutly Protestant David Lloyd George, and Asquith, who rather preferred to imagine that the nation was basking in a long Edwardian summer. These three future Prime Ministers were indifferent at best about the future of Ireland, and since they had such a large majority in the Commons they were not bothered by the concerns of Irish nationalist MPs.

Herbert Asquith, Prime Minister 1908-1916, was indifferent about the Irish question (wikipedia)

In any case, they were too preoccupied charging ahead with a radical reimagination of the role of government, legislating for old age pensions, unemployment benefits and sick pay, among other things. The money for this proto-welfare state had to come from somewhere, and the chancellor Lloyd George had his eyes firmly fixed on the wealthy, and the aristocracy more specifically. His ‘people's budget' in 1909 introduced unprecedented taxes on the wealthy and on landowners, but was struck down by the House of Lords. The resulting constitutional crisis saw the Lords lose their power and the budget passed, but only after the Liberals were forced to call two elections in 1910 to consolidate their mandate. Although they won both elections, their majority in the Commons was reduced to just one seat. To prop up their fragile majority, the Liberal government turned to the Irish nationalists, who had but one demand as their price.

AD:

AMAZON - PADDLING POOL FOR DOGS AND CHILDREN - ONLY £20.99

The Home Rule Crisis

Part of the reform of the House of Lords meant that they could only delay, rather than obstruct, legislation passed by the House of Commons. As long as the same legislation was passed by the Commons for three consecutive years, it would become law in the third year regardless of whether the Lords accepted it.

A Home Rule bill was passed by the Commons in 1912 and duly rejected by the Lords. The same happened in 1913, but the bill was due to pass into law in 1914 regardless of what the House of Lords did. Realising that delay would no longer work, the bill's opponents sprang into action.

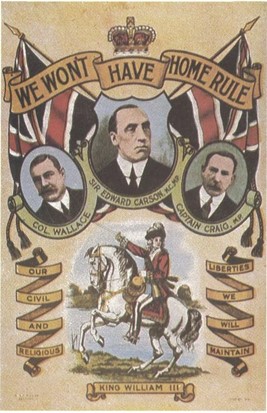

A pro-Home Rule poster (History wiki)

Again, it is important not to oversimplify the story of Irish nationalism and loyalism – this was not a straightforward case of northern Protestants against southern Catholics; indeed, Dublin itself had a large Anglo-Irish, Protestant population which was mixed in its sympathies. But what can be said is that the strongest opposition to the Home Rule bill was to be found in the six predominantly Protestant counties of Ulster, where many people descended from Scottish and English settlers felt complete affinity with mainland Britain and saw Home Rule as a betrayal. Although Ireland would remain in the United Kingdom if Home Rule was passed, these people feared a southern Catholic majority being in charge of Irish affairs.

The opposition to Home Rule – and indeed the complexity of the whole issue – was embodied by Edward Carson. One of the most successful barristers of his day – he had cross-examined fellow Anglo-Irish Protestant Oscar Wilde in his infamous libel trial – Carson hailed from a middle-class Dublin family, spoke with a southern Irish accent, represented a Dublin seat in the House of Commons, and undoubtedly considered himself an Irishman. But he was unabashedly Protestant and pro-union, and was appalled at what he saw as the betrayal of Ireland by the Liberal government.

Meanwhile, in 1911 the Conservative party selected a new leader, Andrew Bonar Law. Born in Canada, he would later become the first British Prime Minister to be born outside of the UK (the second was a certain Boris Johnson). As the son of an Ulster Scots family his commitment to Unionism was heartfelt, and his opposition to Home Rule as genuine as Carson's. However, it would not be a stretch to say that he also saw the political opportunity here; a cause that could unite a divided Conservative party and whip up popular hostility against the Liberals. Law was also frankly terrified of the Liberals, seeing them as no less than ‘revolutionaries' who had hijacked the country. His actions over the Irish question would demonstrate his hypocrisy in this sentiment – in 1912, he proudly declared that he could ‘imagine no length of resistance to which Ulster can go in which I should not be prepared to support them'. Many (correctly) saw this as an endorsement of violent opposition, and the atmosphere was becoming increasingly febrile. Even Winston Churchill was forced to hide from furious unionists when he visited Belfast to promote Home Rule that year.

Edward Carson campaigns against Home Rule (centenaries timeline.com)

Keen to demonstrate that unionism could express itself in a controlled manner, Carson and another Unionist MP, James Craig, developed the idea of an Ulster covenant, in which the unionists of the north would record their determination to oppose the Home Rule bill. ‘Ulster day' was announced in the newspapers, and on 28th September 1912 thousands of Ulstermen and women entered Belfast city hall to sign. By the end of the year, nearly 500,000 people would have signed the covenant.

The Ulster covenant was also a sign of the partition that would eventually be forced on Ireland. Carson would eventually settle for the six Protestant majority counties rather than all nine counties of Ulster being exempt from Home Rule, and the government passed the bill with this exemption in June 1914. King George V signed the bill off in September, but by then the first world war had broken out and domestic politics was effectively suspended.

Was violence inevitable?

As Dan Jackson noted in the Rest is History, the situation was stuck at an impasse by 1914 with neither side likely to back down. The threat of violence was hanging over everything, with the Ulster Volunteers landing a huge shipment of arms in the town of Larne in April. The government in London were concerned about the increasing militarism of the unionists but were equally concerned about where the loyalties of the army lay; with good reason, as it turned out. After asking the commander-in-chief in Ireland, Sir Arthur Paget, to sound out his troops at their base at Curragh Camp, they were dismayed to hear that whole regiments were promising to resign rather than take action against the armed unionists. Interestingly, the press in London seem to have been generally critical of the unionist paramilitaries and the proto-mutiny at Curragh, and Churchill was keen to squash the loyalist rebels; ‘if it comes to rebellion and civil war,', he growled, ‘the government will fight to win it.' However, Churchill's defiance was not shared by his cabinet colleagues, and the government retreated from their hostile stance.

Irish nationalists formed the Irish Volunteer Force and began their own ‘gun-running' operation. By the summer of 1914 both sides were divided into armed paramilitaries – with many officers in the British army indicating that their sympathies were with one side only. It seems that without the first world war a spark would have occurred to ignite a wave of violence across Ireland.

In fact, one only has to look at what happened after the first world war for proof that Ireland was destined for violence. While the spark that would bring violence did not arrive in 1914, it certainly did in January 1919 when Irish politicians declared the first Irish assembly, or Dail Eireann, in Dublin, while on the same day two Royal Irish Constabulary officers were killed in County Tipperary. The resulting two years of violence – of British troops in Ireland, of guerrilla warfare, of atrocities committed by both sides – were likely to have played out five years earlier if the first world war had not interrupted. The conflict is now known as the Irish War of Independence, but since Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom it could arguably be labelled a British Civil War. It had only been delayed, rather than prevented, by the first world war.

Cover image - RGS History