When we think about Quaker owned factories, we often think of the chocolate factories such as Rowntrees, Cadburys and Frys. These companies have a reputation for caring for their workers. Rowntrees is especially noted for creating a poverty survey of York, a lesser known sibling to the more famous London Poverty Maps created by Charles Booth.

However, the Bryant and May factory was the opposite of these Christian based paternalistic businesses. In fact, in the latter part of the nineteenth century, they often hit the headlines and discussions in Parliament for the lack of care and safety offered to their workers. The most notable event that brought the company to public attention was the Matchgirls Strike of 1888.

Before discussing the outcomes of the Matchgirls Strike, it is important to examine the origins of the Bryant and May company and the circumstances that led the women and girls who worked for them taking strike action. William Bryant and Francis May first began working together in 1844, but didn’t make their partnership official until 1852. During this early period, they didn’t produce their own matches, instead they imported premade ones from Sweden. It wasn’t until 1861 that they began producing their own matches in London, which made their business grow until by the 1880s it was England’s largest match producer. Production couldn’t keep up and the company had to open another two factories to keep up with demand. Bryant and May was a popular brand of matches because they were cheap, quick to produce and convenient enough for the consumer to buy. Their popularity meant that the company was able to give their shareholders around 20% or more in dividends.

The life of the ordinary workers in the factory was almost a parallel universe when considering the amount of money the shareholders were being paid. They had to contend with the poisonous fumes created by white phosphorus used to make the matches. Mass exposure to the chemical put them at risk of getting ‘phossy jaw’, a condition that ate away the jaw bones and teeth. The danger of the chemical had been known for years – Charles Dickens, no stranger to the factory environment, wrote about it in 1852, and the extension to the Factory Act in 1864 enforced rules of better ventilation in the match factories. Whilst this did put smaller factories who couldn’t manage with these new regulations out of business, as long as white phosphorus was still in use, ‘phossy jaw’ was still a threat. Out of the twenty-five match factories in the country at the time, only two didn’t use white phosphorus.

As if the risk of death and severe pain from industrial disease wasn’t enough, the workers who worked in the factory, some as young as six-years-old, were expected to work up to fourteen hours a day with only two scheduled breaks. They were fined for many different things such as going to the toilet whilst not on break, untidy workstations, talking and even having dirty feet (despite the fact that many couldn’t afford shoes), reducing their already low wages to a bare minimum. The foremen were also often abusive and never took any complaint to management. For those employed to make matchboxes from their own homes, wages were even worse. Most of the money they earned went towards buying their own glue and string for the matchboxes.

Things finally came to a head in the summer of 1888, when newspapers began to report on the working conditions of Bryant and May. The employers told workers in the company factory in Bow, east London, that they were to refute the allegations or risk losing their jobs. They followed through with their threat on 2nd July, when a female worker was sacked for refusing to deny the newspaper claims.

But what Bryant and May had not counted on was the strength of feeling among their workforce. Almost immediately, over a thousand other workers decided to go on strike, helped by the campaigners Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows, who formed a strike committee on behalf of the striking workers. In total around 1500 workers would strike. The company was known to employ around 2000 people in 1895, of which 1200-1500 of those were women and girls, so this number may well have been their entire female workforce.

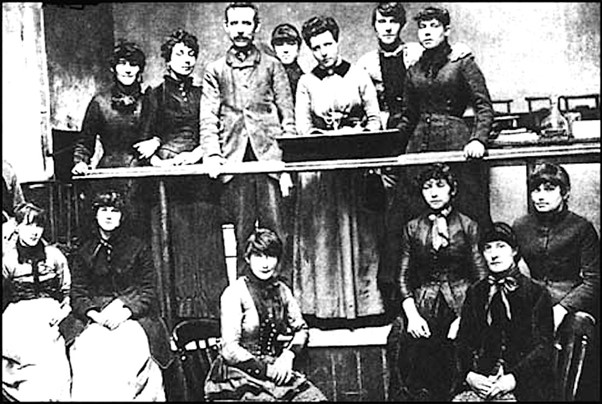

The strikers were led by Annie Besant and Herbert Burrows (Wikipedia Commons)

The strike lasted two weeks and included a march on Parliament demanding change and recognition of their cause. The accusations about the poor pay and working conditions were taken seriously by the public and it received much support, including from powerful bodies such as the London Trades Council. The amount of publicity the cause was getting meant that the factory management had to finally compromise despite their attempts to down play the situation. Most importantly, the fine system was abolished, making wages fairer to all.

The strike highlighted the plight of the working poor and created a desire for change within the match industry, although the ban on white phosphorus from the production process still didn’t happen until 1908.

There were also some changes in attitudes towards factory girls. They were thought to be brash, with low morality and education, but the stories of their treatment showed that they also had generosity and independence. This was helped by stories of matchgirls clubbing together to buy their clothes.

However, not everyone had changed their opinion of factory girls. Following the Strike, the Clifden Institute was set up by Viscountess Clifden for the matchgirls. It offered evening classes, including activities such as needlework and bible studies, a savings bank, club room with books and games, lodgings for twelve girls, and a music hall. This maternalism was no doubt well-meaning but could be seen as patronising, and it was encouraged by the factories because they thought that encouraging discipline and better habits in the female workforce would stop further strikes.

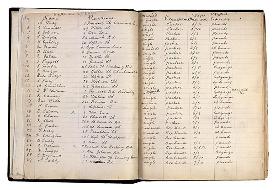

The names of just some of the striking women (Wikipedia Commons)

By far the most useful offering at the Institute was the restaurant. It dished out between 50,000 and 60,000 meals a year, which included meat and two vegetables, and a pudding. This showed that many still were unable to afford to feed themselves.

It was not the end of the troubles for Bryant and May either. They spent most of the 1890s rebuilding their public image, including advertising and magazines to promote themselves as a ‘model company’ who had changed its ways. Whilst this largely worked, there were further allegations in 1892 and 1898 of attempts to cover up deaths and cases of ‘phossy jaw’. They were finally prosecuted in 1898 after the Home Office investigated and found the allegations to be true. Other companies, including a special factory opened by the Salvation Army following the outcry of the 1888 Strike, tried to stop the use of white phosphorus in match production. Unfortunately, the Salvation Army factory found the new process was too expensive and the business soon failed, but the cause for finding less poisonous means of match production still carried on, all thanks to the spark lit by the Matchgirls Strike of 1888.

Danielle Burton is a history blogger and works as a project archive assistant at the Derbyshire Record Office. She has a degree in History and an MA in Public History and Heritage. She has a special interest in Anthony Woodville and the Wars of the Roses, but her blog focuses on little known history. You can visit her blog at https://voyagerofhistory.wordpress.com/ , and find her on twitter @PrincessBurton

References:

Satre, L. J., ‘After the Match Girls’ Strike: Bryant and May in the 1890s’, Victorian Studies, 26.1 (1982), pp. 7-31

Online:

‘The Story of the Strike’, The Matchgirl Memorial, https://www.matchgirls1888.org/the-story-of-the-strike

Brain, J., ‘The Match Girls Strike’, History UK, https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Match-Girls-Strike/